Urban Tribes Artist-to-Watch:

Sarah Haviland- Why Bird?

Why Bird? Wings to effortless historical consciousness

by Luchia Meihua Lee

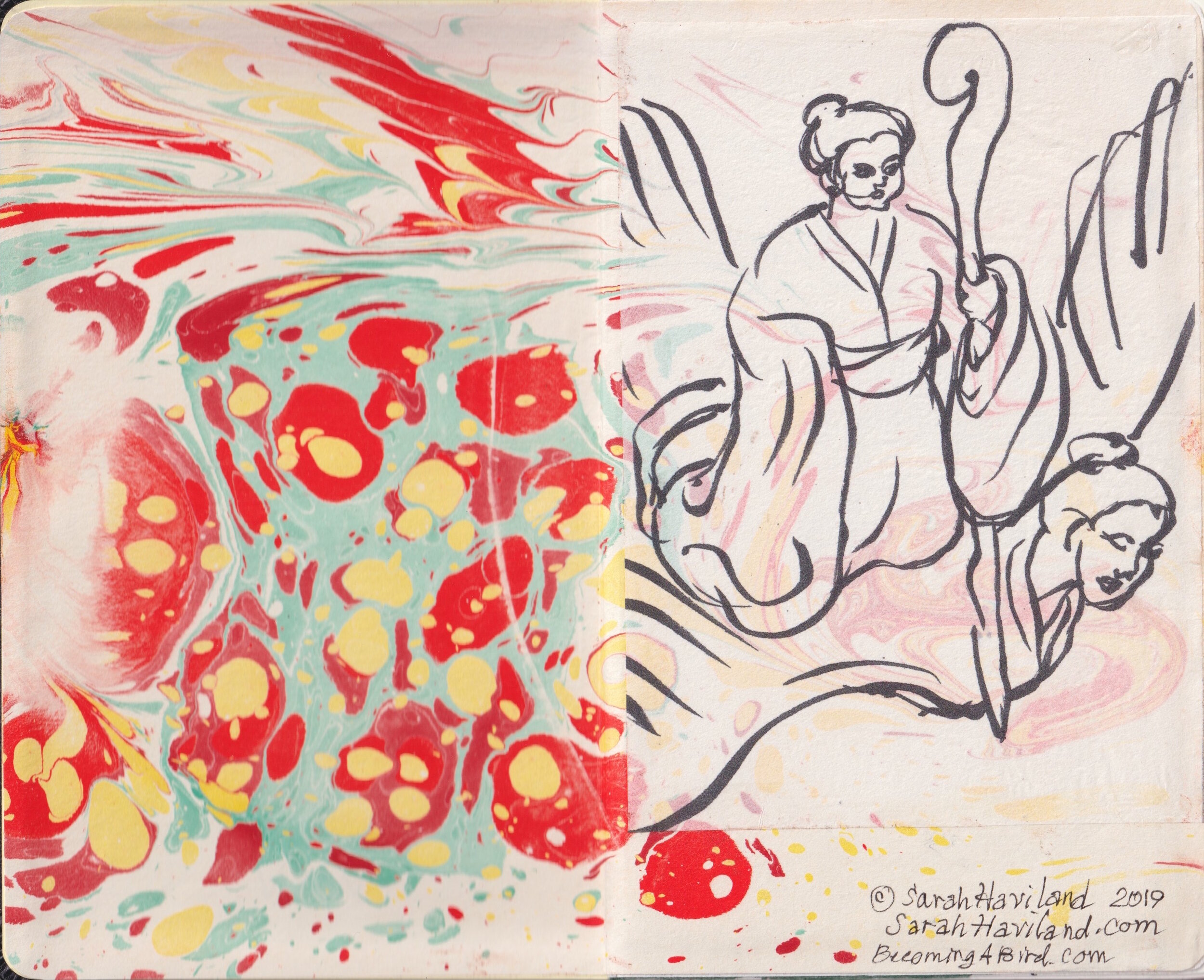

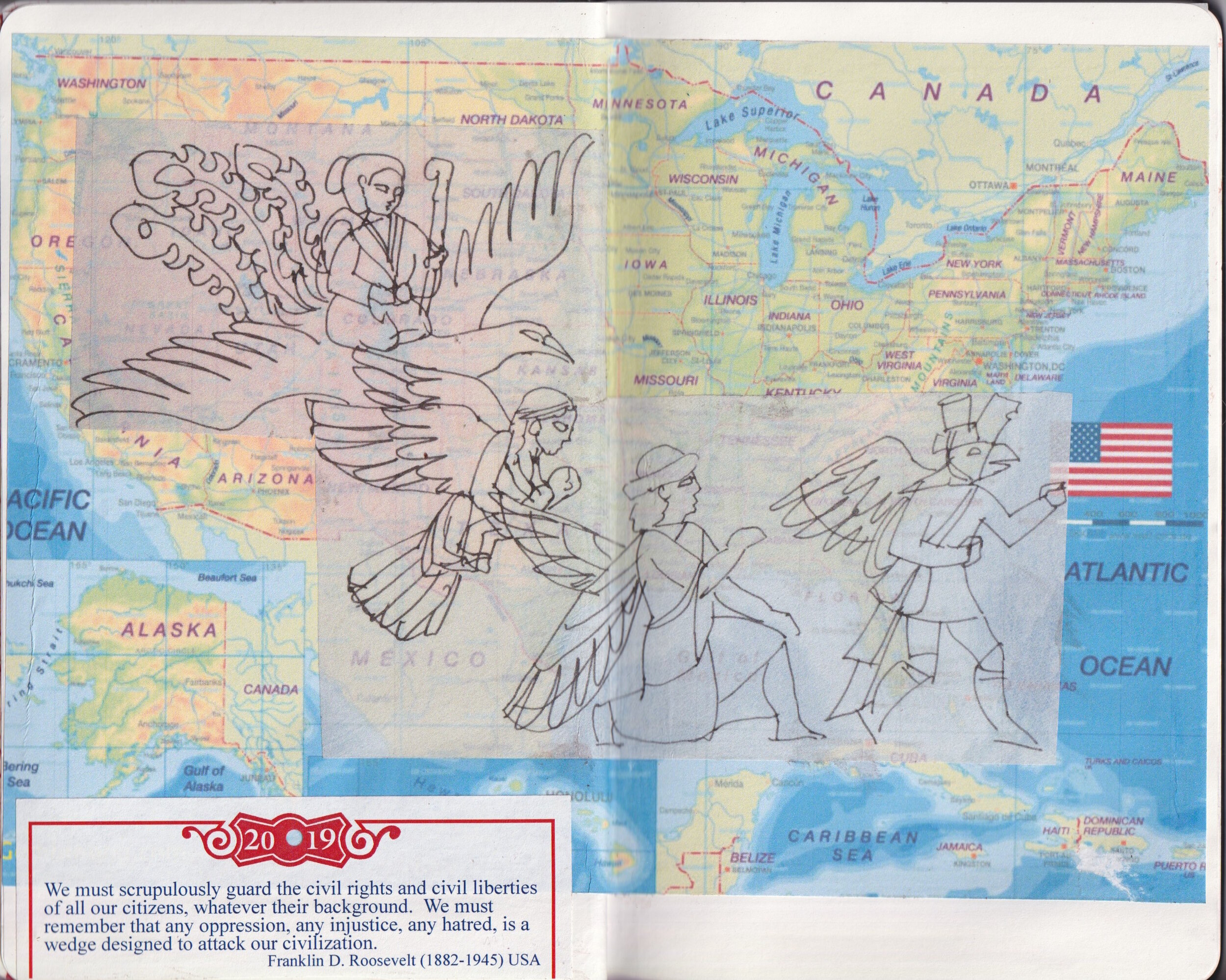

Sarah Haviland creates art that is drawn from the secret recesses of beings to remind us of a root that must never be forgotten. Nuanced humanism and naturalism condition her experience and expression, both domestically and internationally. A Fulbright scholar and multi-talented artist, she flew from the US to reside in Taiwan in 2019 where she taught art and examined temples: rites, architecture, and tradition. Her global research journey produced an artist book of collages that she created to document her artistic and scholarly sojourn in Taiwan.

Here forbearance, I would never attempt or wish to reduce "the notion of mystery in our visual experience and art representation and dissolve the difference between word and image,"[1] or in this case between the various bird images and their allegorical background in an art historical word sense. As Wittgenstein [2] points out, the dichotomy in the famous duck-rabbit image is only available to those able to coordinate pictures and words, visual experience and language. Sarah Haviland's magnificent wings constitute her signature art form, and are not solely an embodiment of her abstract quality but also carry the revived spirit of symbolic sculpture.

With the above remarks firmly in mind, let us disclose the background genealogy of Sarah Haviland's contemporary art, in which she has broken free from complexity in history, ideology, and philosophy to hone in on the essence of visual media and technology. The role of animals in allegory is a journey though art historical relevance by way of symbols, attributes and personification. In early Christian art birds "suggested the 'winged soul' or the spirit, recalling an idea held by the ancient Egyptians that the soul left the body as a bird at death" [3]. One might further appeal to the likeness of the constructed bird image - in effect, the portrait bird - with the female figure in Haviland's earlier works. Her more recent work pursues a more canonically universal cultural aesthetics, where we can find the transformation from an intricate self-consciousness and mental cultivation towards a pronounced outward coordination with the natural environment. The practicality of furniture is invited to flight by wings which appear unexpectedly but organically from the sofa or chair to embrace the sitter. Carrying this idea to its logical conclusion, a chair has been placed up a tree where it hangs in the air. Haviland explored the interstice between angels, birds, and humans in a spectacle of light at the Flatiron Building in Manhattan. She has disentangled from the historical context.

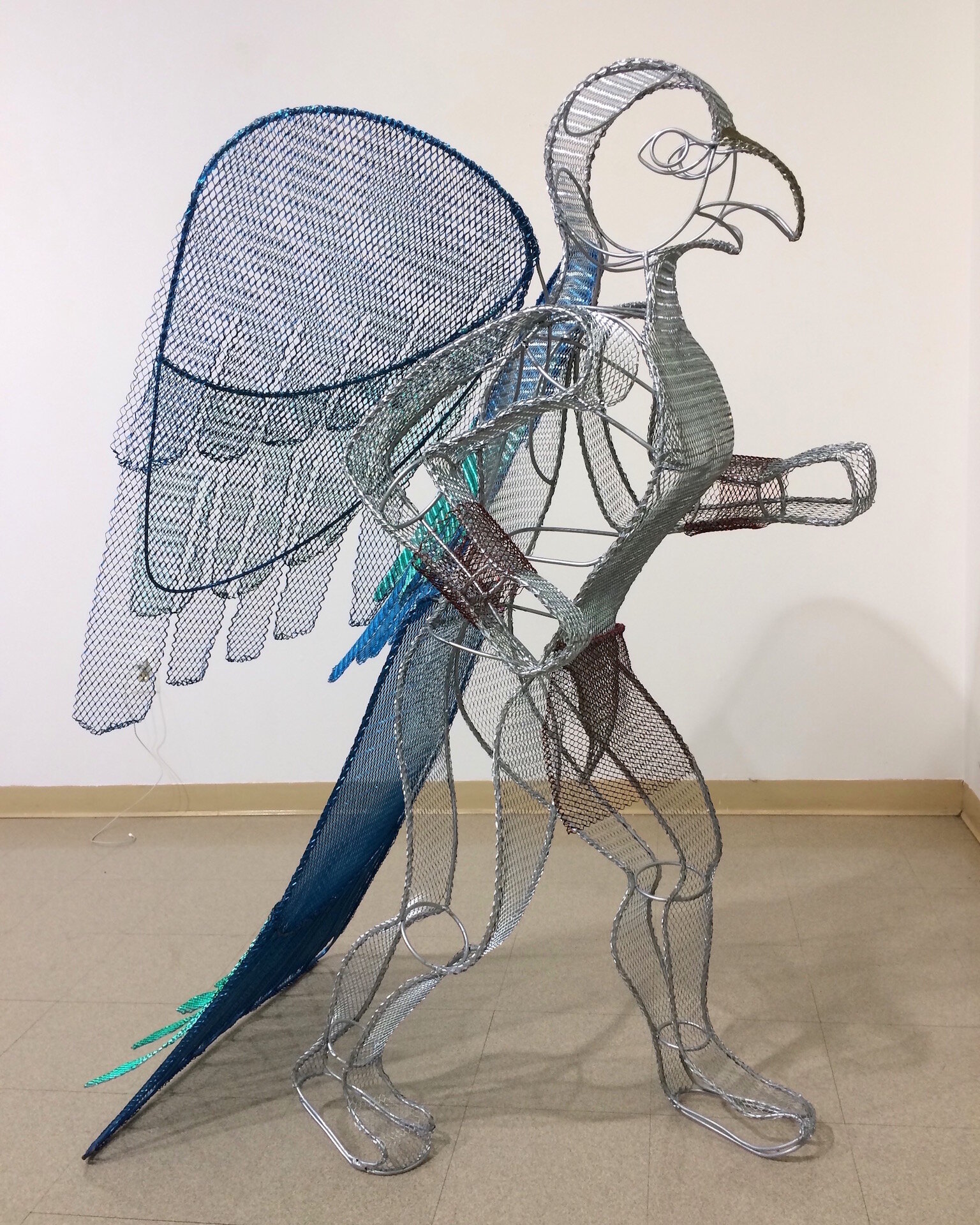

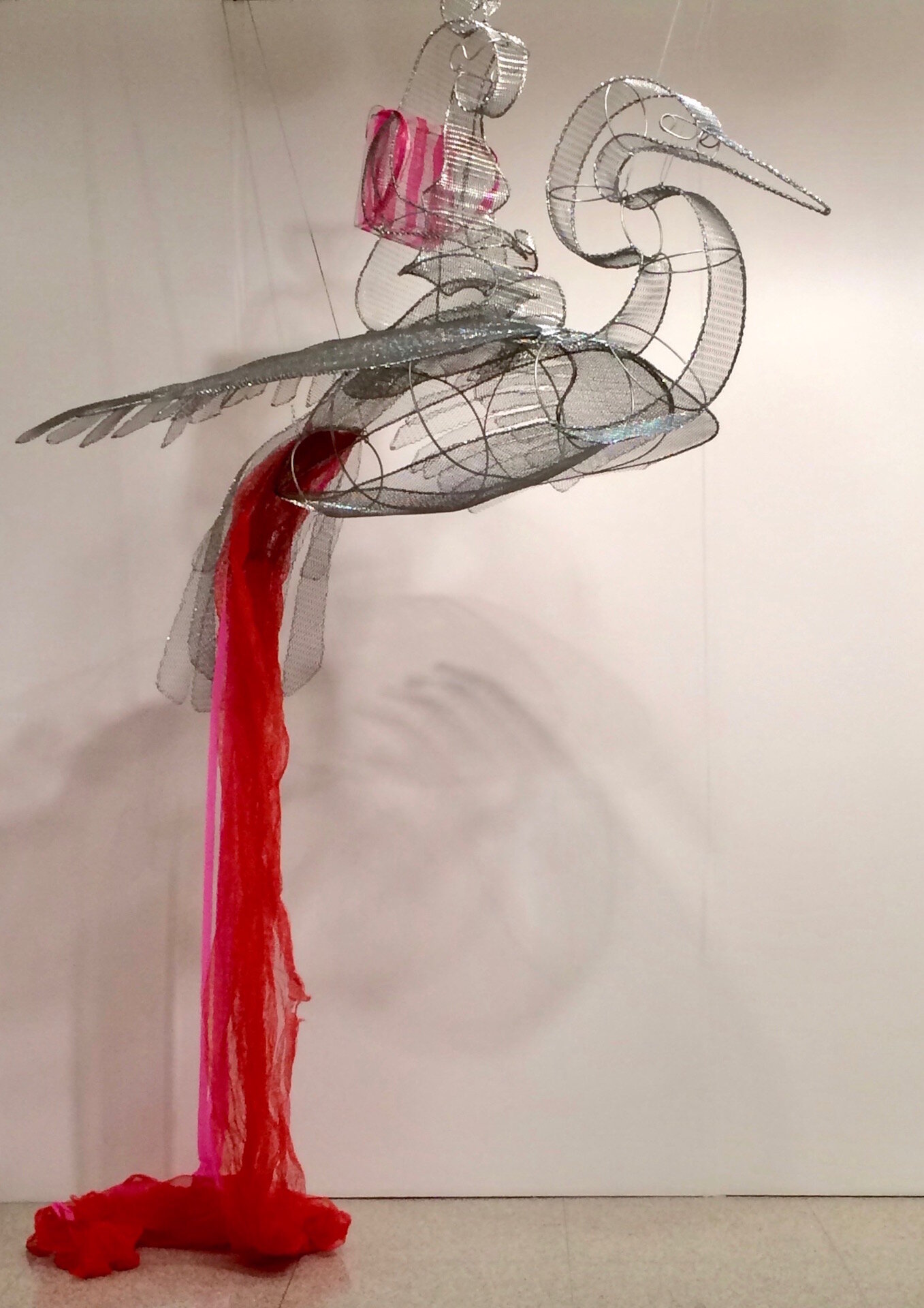

Haviland, in her recurrent use of metal mesh as a material, employs the net, which of course is a contrivance to trap birds. Yet in Haviland's art, metal mesh is porous and airy, and thus has a degree of lightness and effortlessness. Hence, the inorganic participates in implied natural flight, and points indirectly towards human flight. Haviland's birds carry a different character; she captures the emotional effect of transforming sumptuous feather and ornament to simplicity of form. At the same time, the complexity of her art displays the nuances of the translucent web and the air within. Her longing has landed on the grass lawn and turned into an owl perched in a tree and holding a globe.

Moving to a contemporary theoretical view of the subject in general, the form of these winged creatures seems to create a self-understanding within experience in human society. In Foucault's words, three types of technique may be singled out; those that permit one to "produce, to transform, to manipulate things" [4] and it is by the tranformative techniques that a sign system can be revealed in the conduct of individuals. As Foucault remarks, it is the techniques or technology of the self in operation on our own body, mind and thought, which permits individuals to "transform themselves, modify themselves, and to attain a certain state of perfection, of happiness, of purity, of supernatural power, and so on... "[5]. Sarah Haviland brings these meaningful subjects across history and leads to modern concerns and a contemporary accomplishment.

It is impossible not to acknowledge the ever-present birds in Haviland's art and the profound impression made upon the artist by her two sojourns in Taiwan. It is no accident that Chinese mythology (in the Classic of Mountains and Seas) talks about a fabulous creature with the body of a bird and human face. The great beauty of the peacock, with its lavish, and decorative plumage, was a favorite subject for artists throughout the ages. As a token of Juno, it was useful in allegory. The ever-vigilant, powerful eagle was associated with Jupiter "because of its great strength, speed and soaring flight." [6], as the winged lion symbolizes Saint Mark, because the lion represents strength, courage and fortitude, and as a result has long been a royal and aristocratic emblem.

In Chinese mythology, the immortals ride on cranes. Inspired by local folk culture in Taiwan as expressed in temple motifs, Haviland locates this idea by referring to egrets - a frequent sight in Taiwan associated with its favorite locales: the rice field or on the water buffalo's back. She then appeals to the fact that egrets are migratory to suggest that the rider is migratory as well.Turning to the rider, women are associated in Chinese culture with the phoenix, the five-colored bird of wonder. Often used to stand for auspiciousness, it also symbolizes longevity and resurrection (in many cultures, it was supposed to die and be reborn in fire), and appeared in Egyptian mythology as the eternal "Bennu phoenix"; (modeled in fact upon a large heron; but to complete the circle, egrets are a type of heron). It was associated with the sun god and the periodic inundation of the Nile. And thus it was associated with the first inundation that gave birth to the world, from which the bird also symbolized time. The Bennu bird was also linked with Osiris, god of the underworld and of resurrection [7]. The legendary phoenix was also "known" through Herodotus to the Greeks.

Despite the subtext of allegory and historical tradition, I would insist upon the social dimension of Haviland's iconography. Her art is inseparable from environmental concern but in no way subsumed by it.

Notes:

[1] Nelson, Robert S. and Schiff, Richard, Critical Terms for Art History, University of Chicago Press, 1996, pl 49

[2] Wittgenstein, Ludwig philosophical Transactions Translated by G.E.Em Anscombe, Blackwell, 1953

[3] Carr-Gomm, Sarah,The Secret Language of Art, Duncan Baird Publishers, London, 2008, Symbols and Allegories, p. 239

[4] Carette, J. R., Religion and Culture: Michel Foucault, Routledge, 1999, p. 161

[5] Ibid, p. 162

[6] Carr-Gomm, Sarah,The Secret Language of Art, Duncan Baird Publishers, London, 2008, Symbols and Allegories, p. 36

[7] Hart, George. A dictionary of Egyptian gods and goddesses. Routledge & Kegan Paul. 1986. ISBN 0415059097. http://www.egyptianmyths.net/phoenix.htm)